Your Language App Is Optimized for Everything Except Learning

The neuroscience behind why paper still wins

You’ve been on Duolingo for 247 days straight. You can order coffee in Spanish. You can ask where the bathroom is in German.

And yet, when a real conversation starts, your mind goes blank.

Here’s something most people don’t talk about: that little owl hasn’t been completely honest with you. It’s not trying to trick you; it’s just following its programming. But what it’s designed to do isn’t really about helping you learn a language.

I'm not anti-technology

Before you think I’m just anti-technology, I used to code websites in C and PHP when that was still common. I’ve been online since the late 90s. I joined Facebook when it first came to Italy, while most people were still on MySpace, showing off their custom CSS backgrounds.

I’m not anti-technology. I’m writing this on a laptop, not chiseling it into stone tablets.

But somewhere along the way, as the internet became normal and apps took over, we stopped asking if digital tools are truly better or just easier. For language learning, the answer isn’t so simple.

The research is kind of damning, actually

There’s a 2019 meta-analysis that looked at 33 studies comparing reading on paper to reading on screens. In 29 of those studies, people understood better when reading on paper. The difference wasn’t huge, but it was consistent, especially for longer texts or anything that needs real thinking, not just skimming.

There’s also the handwriting factor. Several recent studies show that writing by hand uses more parts of your brain, like memory and motor control, than typing does. One meta-analysis found that about 9.5% more students who take handwritten notes get top grades. It’s not that writing by hand is better in some moral way. It’s just that you have to think about what’s important enough to write down, since you can’t copy everything like you can on a laptop.

Here’s the tricky part: a large meta-analysis of 44 studies involving nearly 150,000 university students found that smartphone addiction measurably reduces academic performance. In some studies, just having your phone off but on your desk still hurts your performance. Simply knowing it’s there distracts you.

For language learning, which relies a lot on working memory, like keeping verb conjugations or sentence structures in mind, this kind of distraction is a big problem.

I’m not making this up to win an argument. These are peer-reviewed studies with huge sample sizes.

Your brain is running prehistoric software

We often forget that human brains haven’t changed much over time. We’re still using the same basic brain our ancestors had when they learned to make tools and remember which berries were safe.

We learn best by using our hands, touching things, and moving through real space to build spatial memory. The digital world is great for many things, but it doesn’t engage these old learning systems well.

That’s why people still buy vinyl records, even though Spotify is much more convenient. Vinyl sales reached $1.4 billion in 2023, even outselling CDs. It’s not just nostalgia. Owning a physical record, putting it on a turntable, and hearing the crackle before the music starts is a ritual that means something to our brains in a way pressing play on Spotify doesn’t.

Same with books. Same with notebooks. Same with—yes—paper dictionaries.

There’s a reason for Japanese tea ceremonies. People spend 20 minutes making pour-over coffee even though a Keurig is faster. These rituals slow us down, and that slowness actually helps our brains. We need time to process information. Going too fast often gets in the way of learning.

The Duolingo trap (sorry, owl)

Look, Duolingo is fine for getting started. It makes the first steps easy. You can do lessons on the bus. The green owl guilt-trips you into showing up every day.

But here’s what happens: to survive as a business, Duolingo needs to keep you engaged. They need you to come back and open the app. Maintaining your streak and clicking on ads, converting to premium.

So the app is designed to keep you engaged, not necessarily to help you learn. The game-like features become the focus. You end up caring more about your 247-day streak than about real conversations. Lessons are getting shorter and more bite-sized because attention spans are shrinking, and apps have to compete with TikTok and Instagram.

Algorithms have trained us, much like Pavlov’s dogs, to scroll for instant rewards. Duolingo fits right into that same cycle. It’s not the app’s fault; it’s just doing what it needs to do to survive in today’s attention economy.

A paper grammar book doesn’t have this problem. It achieved its goal the day you bought it. It’s not trying to hook you. It’s not tracking your engagement metrics. It just... sits there. Waiting for you to open it when you need it.

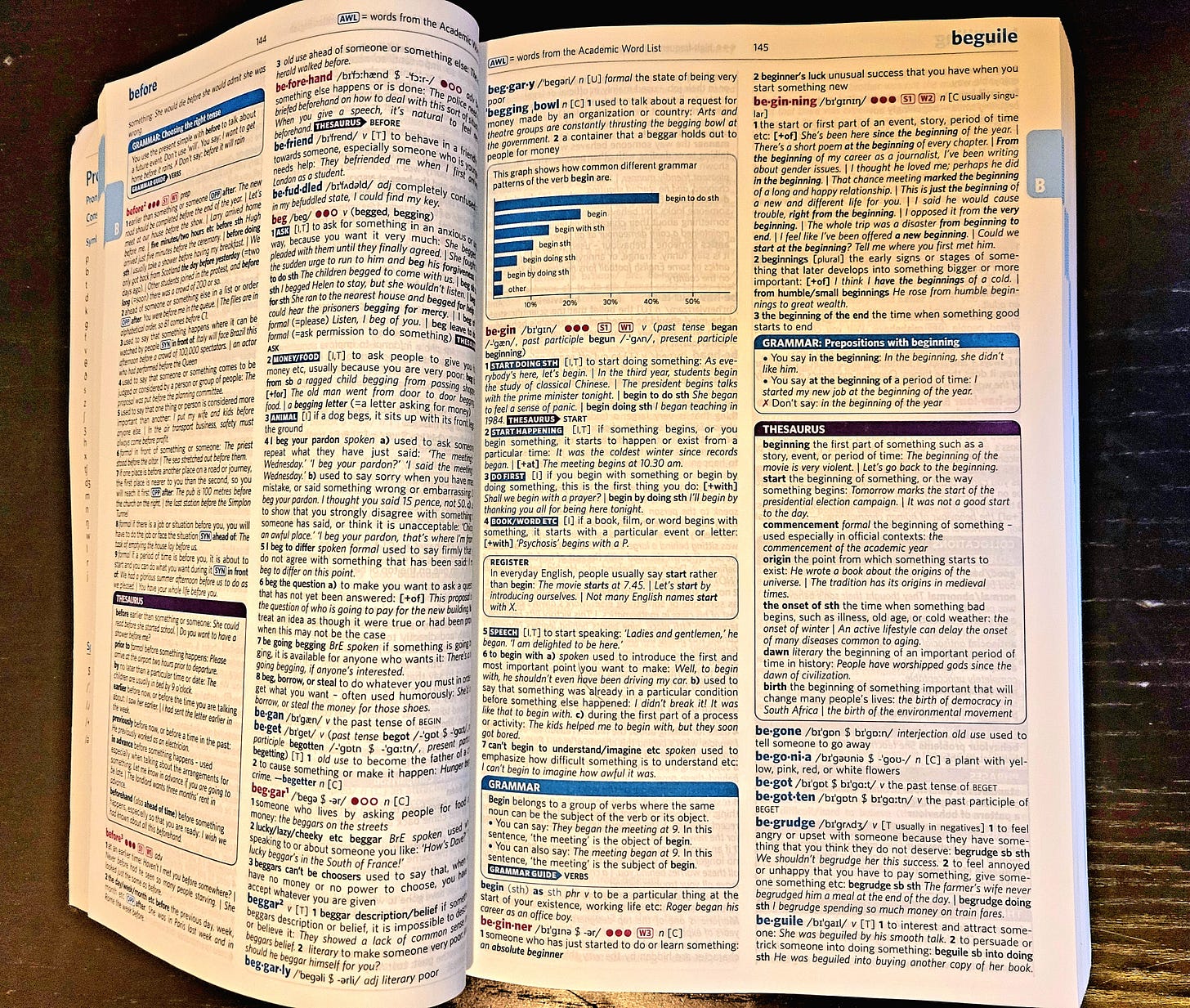

Why I keep a paper dictionary on my desk (and with a bit of effort, I actually use it)

Learning a language deeply isn’t about consuming content. It’s about building structure in your brain. Understanding patterns. Noticing exceptions, sitting with confusion until something clicks.

Paper tools are actually good at this because they’re harder to use.

Looking up a word in a paper dictionary takes more time. You flip through pages, and while searching, you notice other words nearby. Sometimes you get distracted and read entries you didn’t plan to. It might seem inefficient, but it actually helps your brain make new connections.

Google Translate gives you the answer instantly, which is excellent when you need the answer. But terrible for learning, because your brain doesn’t have to do any work. Plus, translations are often wrong.

Writing notes by hand works the same way. It’s slower, and your hand might cramp, but the physical effort, along with deciding what’s important to write, helps you remember better.

Distraction is like having cookies in the house when you’re trying to eat healthy. If there are no cookies, you don’t need willpower. If your phone isn’t on your desk, you won’t be tempted to check it every few minutes.

As I write this on a laptop, I keep getting distracted by tabs, notifications, and the urge to check email. If I were writing by hand in a notebook, I’d be much more focused. The tool you use affects your behavior.

Why 'just immerse yourself' isn't enough

There’s this popular idea that you don’t need grammar books or formal study. Just immerse yourself and pick it up naturally, the way kids do.

And yeah, immersion works. You can absolutely become conversational through exposure alone. I’ve seen videos of immigrants who learned Italian or German perfectly fluently, complete with regional accents and hand gestures. Impressive as hell.

But what people often don’t mention is that these speakers usually have a limited vocabulary and weaker grammar. They can handle daily life, make friends, and work, but they eventually reach a limit.

High-level professional work, such as writing contracts, using medical terminology, or giving academic presentations, requires precision. You have to understand the formal way of speaking, not just the casual one. That’s often the difference between a $40K job and a $120K job. It’s not that one way of speaking is better, but some opportunities only come if you can switch between different styles.

Grammar books are boring. Nobody’s going to argue otherwise. But they give you a map of how the language works. They make explicit the patterns that native speakers absorbed unconsciously over the years. And for adult learners who don’t have years to spend, that explicitness is valuable.

The best grammar books, often the old-fashioned paper ones, are still some of the most reliable ways to build that kind of structural understanding.

What actually works (from someone who’s tried everything)

Okay, practical stuff:

Keep your phone in another room when you study. Not on silent. Not face-down on the desk. In another room. I know this sounds extreme. Do it anyway. The research is clear: even a turned-off phone tanks your cognitive performance just by being visible.

Have at least one good paper grammar book. It doesn’t need to be new. Used bookstores have great language textbooks from the 70s and 80s that are often better than most modern apps. If you feel like you’re wasting time flipping through it, you’re not. That’s your brain processing.

Write things by hand sometimes. Not everything, of course, but key verb conjugations, example sentences you want to remember, and mistakes you keep making. The act of writing helps you remember in a way typing doesn’t.

If you use apps, treat them as tools, not games. Turn off all notifications. Use them on a computer instead of your phone when you can. Computers are less distracting than phones. Set a timer, and when it goes off, stop, even if the app encourages you to continue.

Accept that being slow is okay. Looking up words in a paper dictionary takes longer than using Google Translate. Writing by hand is slower than typing. Reading a physical book is slower than using an app. But that slowness isn’t wasted time; it’s your brain actually learning.

Here’s the bottom line

Paper isn’t magic. It’s not morally superior to screens. But it has properties that align better with how human brains actually learn difficult things.

Digital tools are excellent for exposure, listening practice, and connecting with native speakers. Apps have their place. I’m not saying throw your phone in a river and move to a monastery.

But when you need to build a deep understanding, when you want to train your brain to think in another language rather than just translate, physical tools still work better. It’s not because they’re old-fashioned, but because they make your brain work harder in ways that count.

The owl will disagree. But the owl has a 247-day streak to protect.

What’s worked for you? Have you noticed any difference between learning on paper versus screens? I’m genuinely curious—hit reply and let me know.

Yes! I totally believe that different people learn different ways and what works for one learner might not work for another. Our goals are all different, too, so for some people just having a chat or being able to order a coffee might be enough. However, at some point on our individual language learning journeys, most people will benefit from slowing down and writing by hand. Personally, I don't think there's anything wrong with playing games on Duolingo, especially if you're just starting out with a new language, but if you decide to continue, your results will correspond to the effort you put in. The friction makes it stickier! Thank you so much for sharing this article!

I’m in the process of learning English on my own. I’ve also used apps for that, and I totally agree they’re not tools to speak fluently, more like a support for studying. Still, I wanted to share my perspective here.

The switch from paper to screen shouldn’t be seen as a loss of quality, but as a change in nature. A shift in format that makes us adapt, just like when authors went from manuscripts to print. Back then, some people probably saw printed books as "soulless", forgetting that writing has always been about combining technique, medium, and adaptation.

Beyond what certain journalistic studies may claim, empirical evidence suggests that writing by hand versus on a keyboard doesn't mean the brain is used more or less. Rather, the difference is qualitative. Writing by hand is, in essence, drawing. It's a process of graphic construction that activates more integrated functional connectivity networks. While the keyboard optimizes spatial location and speed, manual writing requires a motor precision that facilitates deeper information encoding. Given that our prehistoric brain doesn't have specific functions for reading and writing, it makes sense to use both methods to expand our cognitive range and integrate tools into our biology. At the end of the day, learning depends more on the quality of texts and our ability to imitate than on the format.

Our brain isn’t a simple organ. We’re the result of an evolutionary chain that gave us an amazing ability to focus, even with constant distractions. We work as a full organism, where the mind-body connection matters (Damasio, 1994).

So we should move away from the speed and effort fallacy. It’s not about how fast we are, but about how well we turn information into meaningful learning through comparison and experience. For example, if you tell a kid a planet is a sphere instead of showing them a ball, the knowledge stays abstract.

Effort is key for resilience, but sacrifice doesn’t automatically mean it’s healthy or efficient. Aim for efficiency. Get the same result with well-directed effort. That’s a sign of evolutionary intelligence. And I totally agree that a slow, well-done process is way better than a rushed mess.

Grammar works the same way. It’s an essential tool to understand language, but how useful it is depends on what you want to do with it. Learning something you don’t use is basically a waste of energy. Sometimes we romanticize classical styles and their contemplative pace, forgetting that every era has its own trends. Digression used to be valued. Today, speed is valued. Both have their rewards, but the real challenge is adapting to sedentary lifestyles and technology that moves faster than our biology.

More than ever, we need to push ourselves to adapt, to live fully in this world, not just survive in it.

I really appreciate your text. While I’m learning the language, your experience has been really helpful and made me think about my own perspective. Seeing how others learn also helps us understand and value differences, and gives us more options for our own lives.

Cheers to everyone!